COSYNE 2020 Impressions

This year’s COSYNE had great content in all areas of computational neuroscience. In this post we give highlights of some of the posters, talks, and workshop sessions that we found to be interesting or relevant.

T-1 Deep reinforcement learning and its neuroscientific implications. Matt Botvinick

Just as deep learning got reinvigorated with the introduction of AlexNet, reinforcement learning (RL), or more specifically Deep RL, exploded after Deep Mind’s Alpha Go paper. Deep RL is a hot area of research with many scientific uses and implications. In Matt’s talk, he stressed to the audience that Deep RL also has implications for neuroscience as well. Just as deep neural networks have been used as models for certain areas of the brains, Matt said that Deep RL can also be used as models for how we solve tasks. From there he showcased a bevy of examples where Deep RL utilized techniques that were strikingly similar to what is done in the brain, very a la Mante & Sussillo, and how these models can also be used to make predictions about what is done.

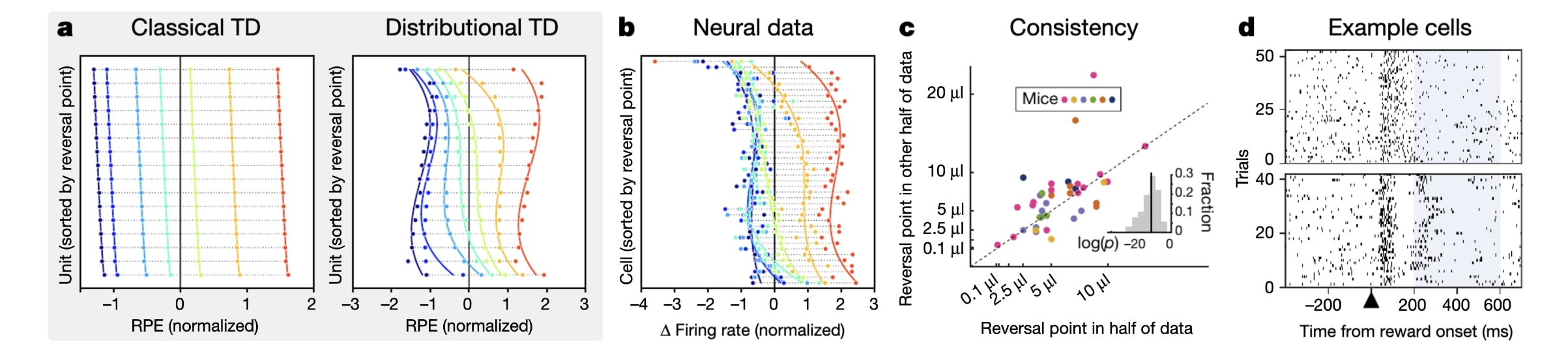

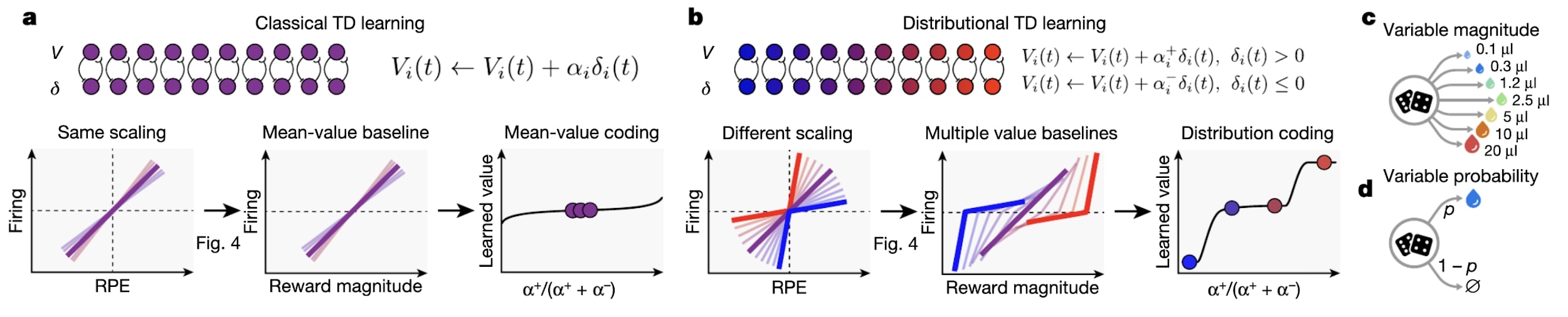

The most compelling example to me was the connection between Deep RL using distributional TD-learning (reward values are now random variables as opposed to deterministic functions of the state and action) and dopamine neurons. They showed that an agent employing distributional TD-learning had neural signals that were super close to signals recorded from actual dopamine neurons. They then opened the DNN and found that the tuning curves were elbow shaped. They then posited a hypothesis about the rate of change of the tuning curves and the reward received. This hypothesis was tested in vivo and it turned out to be true which was insanely cool!

The most compelling example to me was the connection between Deep RL using distributional TD-learning (reward values are now random variables as opposed to deterministic functions of the state and action) and dopamine neurons. They showed that an agent employing distributional TD-learning had neural signals that were super close to signals recorded from actual dopamine neurons. They then opened the DNN and found that the tuning curves were elbow shaped. They then posited a hypothesis about the rate of change of the tuning curves and the reward received. This hypothesis was tested in vivo and it turned out to be true which was insanely cool!

I-64 A framework for unifying and generalizing models of neural dynamics during decision-making. David Zoltowski, Jacob Yates, Jonathan Pillow, Scott Linderman

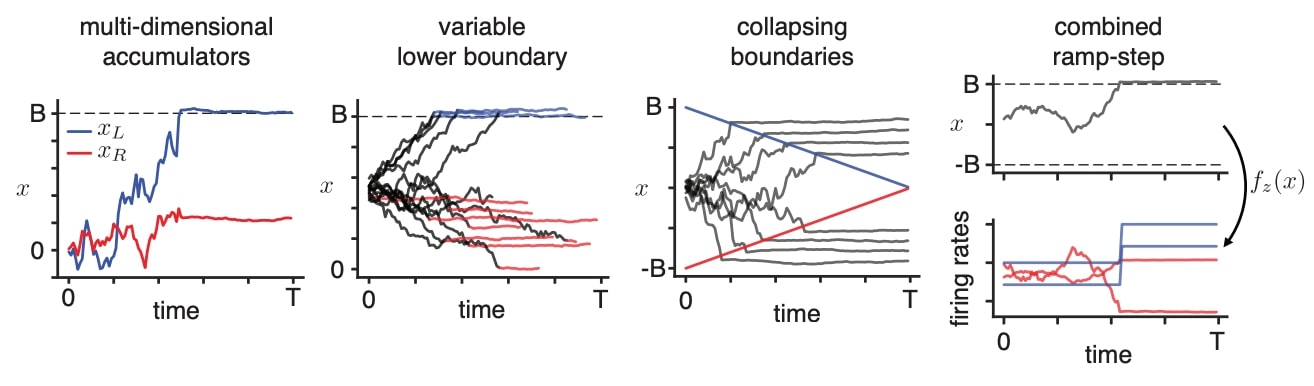

They found that the recursive switching linear dynamical systems (rSLDS) model is flexible enough to encompass a wide array of theoretical evidence-accumulation / decision-making models. Therefore, they can do a bottom-up theory comparison and discovery from spike train observations. They further developed a fast Bayesian method called variational Laplace-EM to overcome the limitations of the original Gibbs sampling based inference in [Linderman 2017]. The method uses conditional independence assumptions to separately perform filtering over the states.

The authors use a variational EM approach to infer the discrete states and the Laplace method to infer the distribution over the continuous latents. The authors then test their inference method by fitting a ramp model with a variable lower bound to data from Roitman and Shadlen (2002), see figure.

The authors use a variational EM approach to infer the discrete states and the Laplace method to infer the distribution over the continuous latents. The authors then test their inference method by fitting a ramp model with a variable lower bound to data from Roitman and Shadlen (2002), see figure.

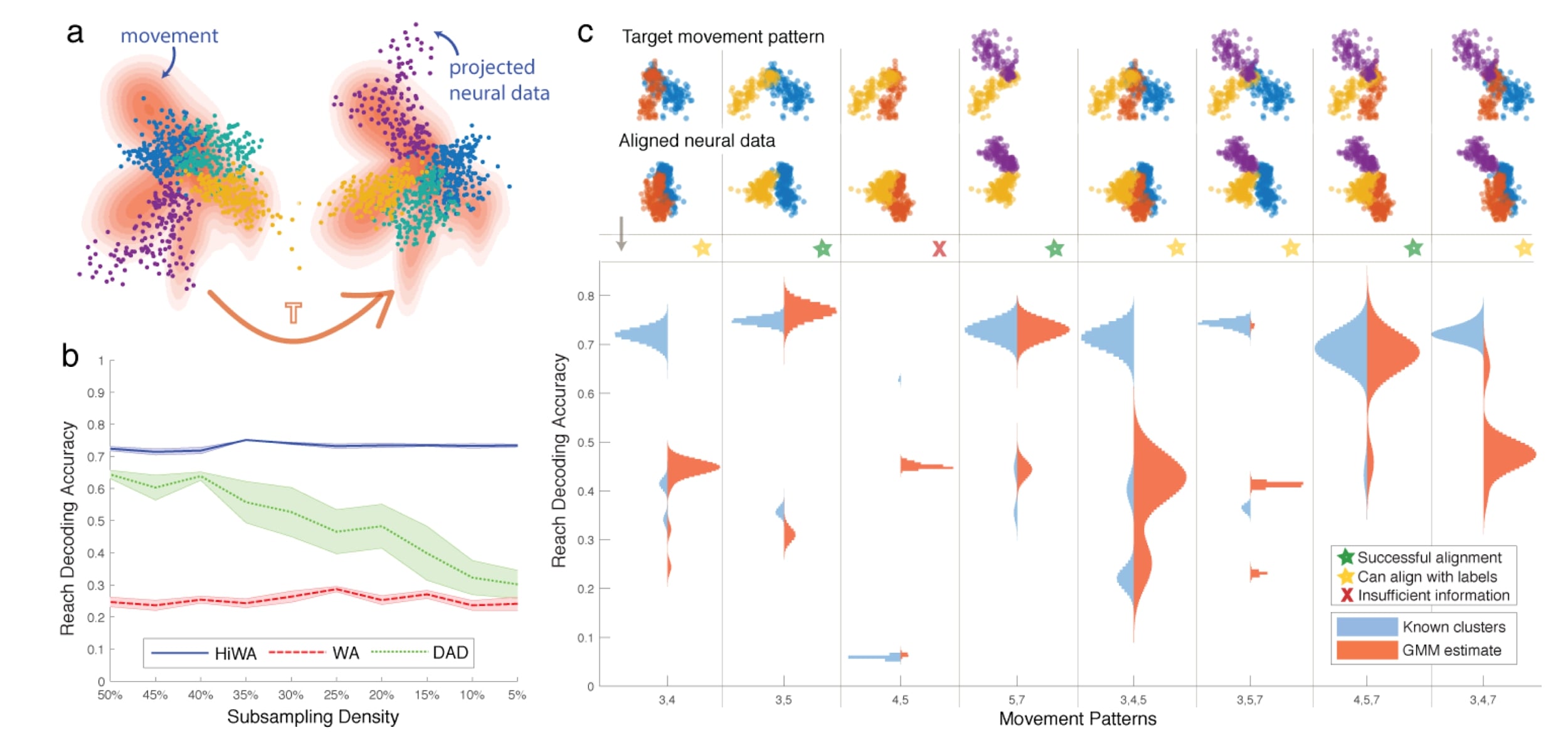

I-124 Neural distribution alignment via hierarchical optimal transport. Max Dabagia, Eva Dyer

The author developed an approach to align, for example, the extracted latents (eg. x and y) of different sessions or animals by dimensionality reduction methods. Using Wasserstein divergence, they quantify the distance between distributions lying on subspaces, and identify similar subspaces based on this notion of distance, argmin_T W(T(x), y). The transformation to align two low-dimensional, linear subspaces has a closed form. Aligning sessions sounds useful. By the presentation, they require x and y to be of the same dimensionality.

II-7 Theory of gating in recurrent neural networks. Kamesh Krishnamurthy, Tankut Can, David Schwab

The use of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) as a means to study the structure and time dependencies of sequential data has a relatively long history in the field. However, due to the difficulties involved in training more traditional architectures, such as the standard vanilla RNN, many have turned to the implementation of gated architectures, which have been shown to significantly improve performance. While empirically the effectiveness of such network structures is recognized, very little in the way of underlying theory exists. Using dynamical mean-field theory (DMFT), the authors begin to close that gap. They begin by looking at the underlying continuous-time vanilla RNN and extend the model to incorporate two gating mechanisms, the update gate (z-gate) and output strength gate (r-gate). Note that these gates are themselves changing in time, but setting the coefficient associated with their derivatives equal to zero simplifies the system to the form of the continuous-time gated recurrent unit (GRU). By combining mean-field theory with random matrix theory, the spectral curve of the state-to-state Jacobian matrix of the local dynamics could be calculated, and the influence of both gates on this curve could be studied.

What was found is that increasing the influence of the z-gate in a local neighborhood results in the leftward shifting and pinching of the right side of the spectral curve to the origin on the complex plane, thereby moving eigenvalues with a positive real part to the left half plane. However, this may force many of the eigenvalues to cluster near the origin, resulting in regions of marginal stability in the infinite width limit, oftentimes acting as a MFT separatrix between stability and chaos. Furthermore, increasing the influence of the r-gate results in an increase in complexity within phase space, and aids in the generation and transition to chaos. The authors then turn to the gates’ effects on long-term behavior. The full Lyapunov spectrum was calculated, and a condition for the transition to chaos was formulated, along with the phase plot of the network with regions of marginal stability included.

What was found is that increasing the influence of the z-gate in a local neighborhood results in the leftward shifting and pinching of the right side of the spectral curve to the origin on the complex plane, thereby moving eigenvalues with a positive real part to the left half plane. However, this may force many of the eigenvalues to cluster near the origin, resulting in regions of marginal stability in the infinite width limit, oftentimes acting as a MFT separatrix between stability and chaos. Furthermore, increasing the influence of the r-gate results in an increase in complexity within phase space, and aids in the generation and transition to chaos. The authors then turn to the gates’ effects on long-term behavior. The full Lyapunov spectrum was calculated, and a condition for the transition to chaos was formulated, along with the phase plot of the network with regions of marginal stability included.

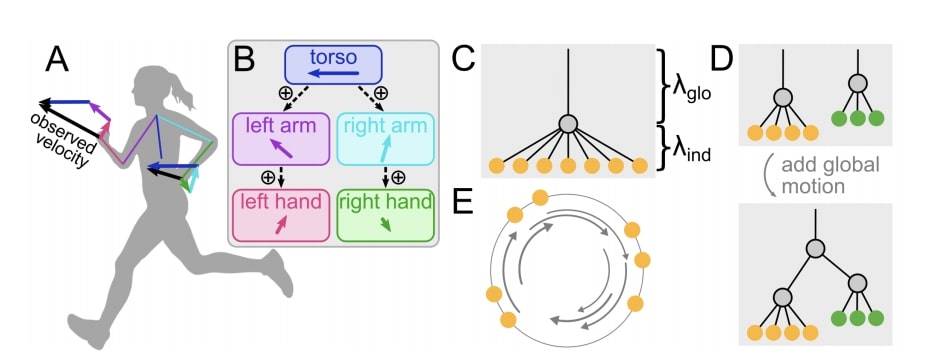

II-14 Human visual motion perception shows hallmarks of Bayesian structural inference. Sichao Yang, Johannes Bill, Jan Drugowitsch, Samuel J. Gershman

relevant paper

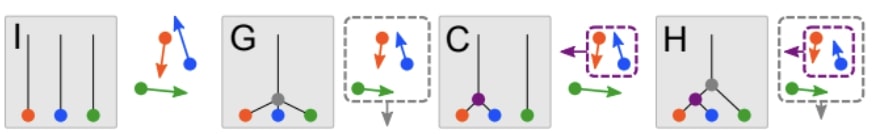

In our day to day lives, our visual system analyzes complex motion data from the outside and parses out relevant statistical features and structure to aid us in the task at hand. One such structure is motion grouping which corresponds to a group of objects whose motions are statistically dependent. To see if humans do indeed parse out structure, more specifically in a Bayesian manner, the authors designed the following experiment to test their hypothesis. The experiment consists of 3 dots moving on a circle where the structure of the motion grouping can fall into one of the 4 categories.

In our day to day lives, our visual system analyzes complex motion data from the outside and parses out relevant statistical features and structure to aid us in the task at hand. One such structure is motion grouping which corresponds to a group of objects whose motions are statistically dependent. To see if humans do indeed parse out structure, more specifically in a Bayesian manner, the authors designed the following experiment to test their hypothesis. The experiment consists of 3 dots moving on a circle where the structure of the motion grouping can fall into one of the 4 categories.

A Bayesian observer model was also fit to compare the data between humans and the Bayesian observer model. The authors’ findings show that humans are able to identify the motion grouping structure from observing the 3 dots. Moreover, they found that the humans performance can be explained very well by the Bayesian observer model, providing empirical evidence that humans do perform Bayesian structural inference on motion data.

A Bayesian observer model was also fit to compare the data between humans and the Bayesian observer model. The authors’ findings show that humans are able to identify the motion grouping structure from observing the 3 dots. Moreover, they found that the humans performance can be explained very well by the Bayesian observer model, providing empirical evidence that humans do perform Bayesian structural inference on motion data.

II-19 Attractor dynamics gate cortical information flow during decision-making. Lorenzo Fontolan, Arseny Finkelstein, Michael Economo, Nuo Li, Sandro Romani, Karel Svoboda

The authors want to study robustness of decisions about future actions. They perform optogenetic stimulation of genetically defined neurons in vibrissal somatosensory cortex (vS1) while recording from this area and anterior lateral motor cortex (ALM). A photostimulus applied to left vS1 during the sample epoch (delineated by auditory cues) instructed mice to lick right, whereas the absence of a photostimulus instructed mice to lick left.

The authors want to study robustness of decisions about future actions. They perform optogenetic stimulation of genetically defined neurons in vibrissal somatosensory cortex (vS1) while recording from this area and anterior lateral motor cortex (ALM). A photostimulus applied to left vS1 during the sample epoch (delineated by auditory cues) instructed mice to lick right, whereas the absence of a photostimulus instructed mice to lick left.

They find that sensory-related information was transient and peaked first in vS1, followed by activation in ALM. Choice-related information was nearly absent in vS1, but emerged in ALM early during delay and increased with time. Then they train mice in the same task and probed behavior in the presence of weak/strong distractors (weak photostimuli delivered at different times). Distractors during early delay significantly increased wrong responses while late-delay distractors did not affect behavior, an effect they call temporal gating. The neuronal activation doesn’t attenuate in either vS1 or ALM at different phases of task.

They find that sensory-related information was transient and peaked first in vS1, followed by activation in ALM. Choice-related information was nearly absent in vS1, but emerged in ALM early during delay and increased with time. Then they train mice in the same task and probed behavior in the presence of weak/strong distractors (weak photostimuli delivered at different times). Distractors during early delay significantly increased wrong responses while late-delay distractors did not affect behavior, an effect they call temporal gating. The neuronal activation doesn’t attenuate in either vS1 or ALM at different phases of task.

After performing dimensionality reduction, the authors see that neural activity switches from one trajectory to the other when decision changes. The authors hypothesize that stimuli can reach ALM and perturb the motor plan throughout the delay, but the motor plan becomes progressively more robust as the moment to act approaches. Finally they train an RNN that reproduces data and reverse-engineer it. They find that each choice is represented by an attractor (separated by a saddle) and temporal gating arises as these 2 attractors become more separated with time.

After performing dimensionality reduction, the authors see that neural activity switches from one trajectory to the other when decision changes. The authors hypothesize that stimuli can reach ALM and perturb the motor plan throughout the delay, but the motor plan becomes progressively more robust as the moment to act approaches. Finally they train an RNN that reproduces data and reverse-engineer it. They find that each choice is represented by an attractor (separated by a saddle) and temporal gating arises as these 2 attractors become more separated with time.

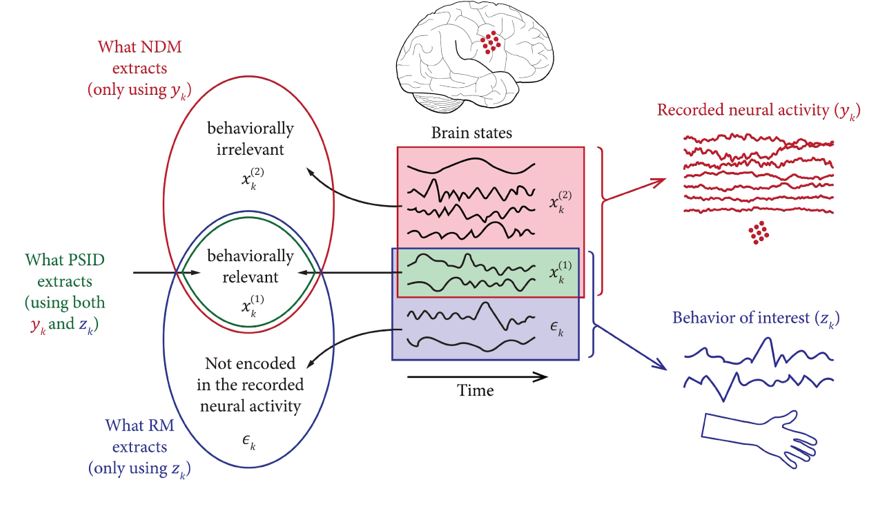

II-83 Modeling behaviorally relevant neural dynamics with a novel preferential subspace identification (PSID). Omid Sani, Bijan Pesaran, Maryam Shanechi

The authors develop a novel preferential subspace identification (PSID) algorithm that models neural activity while dissociating and prioritizing its behaviorally relevant dynamics. The problem was formulated as state space models.

Assuming a linear mapping between latent and observation (combining neural activity and behavior), they decompose the latent dimensions into behavior relevant and behavior irrelevant components, and the behavior dynamics also contain a component that is not present in the neural recording.

PSID in the first stage extracts behaviorally relevant latent states by projecting the future behavior onto the past neural activity (regression), in the second stage first finds the part of the future neural activity that is not explained by the extracted behaviorally relevant latent states, i.e., does not lie in the subspace spanned by these states (residuals).

Assuming a linear mapping between latent and observation (combining neural activity and behavior), they decompose the latent dimensions into behavior relevant and behavior irrelevant components, and the behavior dynamics also contain a component that is not present in the neural recording.

PSID in the first stage extracts behaviorally relevant latent states by projecting the future behavior onto the past neural activity (regression), in the second stage first finds the part of the future neural activity that is not explained by the extracted behaviorally relevant latent states, i.e., does not lie in the subspace spanned by these states (residuals).

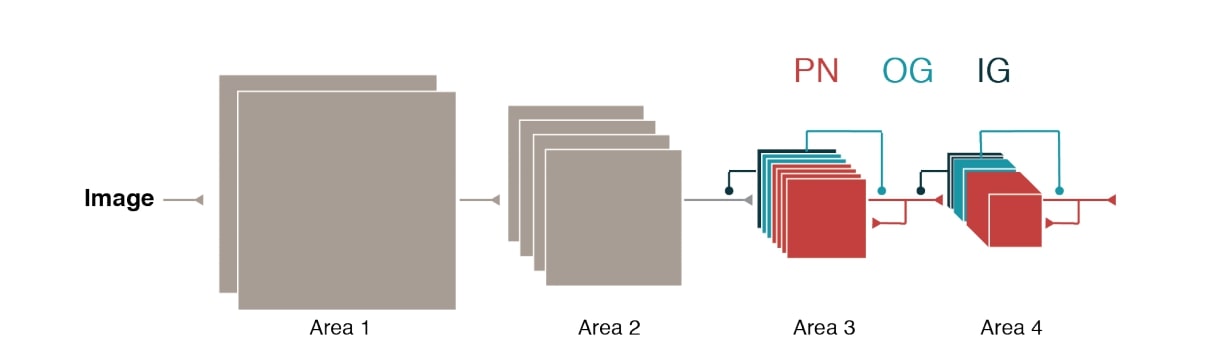

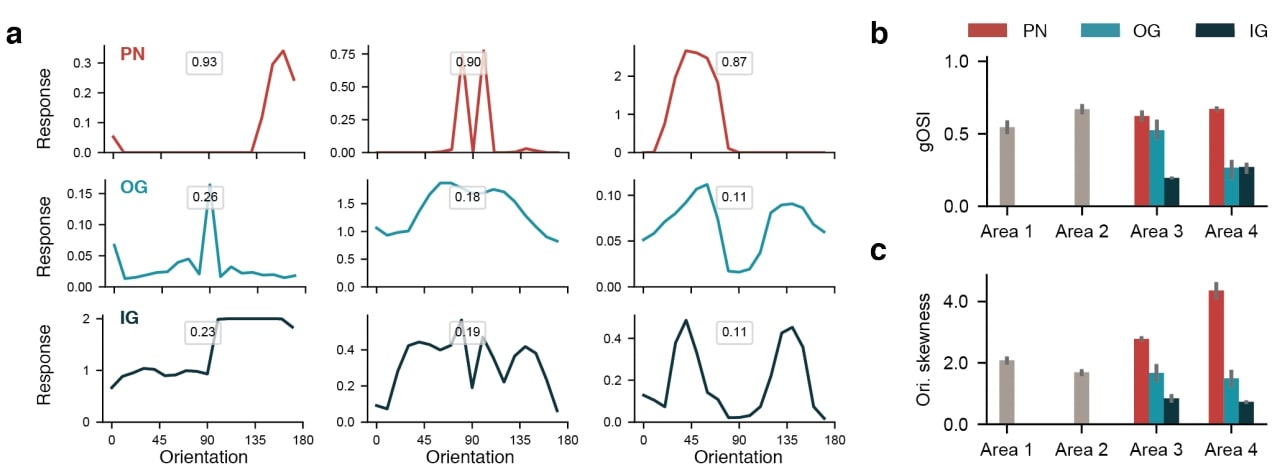

II-116 Understanding the functional and structural differences across excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Sun Minni, Li Ji-An, Theodore Moskovitz, Grace Lindsay, Kenneth Miller, Mario Dipoppa, Guangyu Robert Yang

Minni et al. propose a convolutional recurrent neural network architecture based upon the separation of inhibitory and excitatory neurons stated by Dale’s law. The author does this by training the network to respect biological constraints such as Dale’s law, the abundance of excitatory neurons, and excitatory as principal (or projection) neurons. In order to impose these biological constraints the ConvLSTM architecture of Xinjiang et al. is modified by the addition of input-gating (IG) and output-gating (OG) neurons that feed into the more standard input and output gates. Additionally, the classical hidden state is replaced by the notion of a principal neuron (PN).

To keep true to the nature of inhibitory and excitatory neurons, IG and OG gate neurons all make inhibitory connections by keeping the associated weight matrices negative, and PN connections are made excitatory by keeping the associated weight matrices positive (done using an absolute value constraint rather than using ReLU’s). On CIFAR-10 the network is able to perform similarly to more standard architectures of similar depth. With this same experiment it is also shown that PN’s exhibit high selectivity (shown by their high gOSI and skewness metrics) and have sparse connectivity to one another.

To keep true to the nature of inhibitory and excitatory neurons, IG and OG gate neurons all make inhibitory connections by keeping the associated weight matrices negative, and PN connections are made excitatory by keeping the associated weight matrices positive (done using an absolute value constraint rather than using ReLU’s). On CIFAR-10 the network is able to perform similarly to more standard architectures of similar depth. With this same experiment it is also shown that PN’s exhibit high selectivity (shown by their high gOSI and skewness metrics) and have sparse connectivity to one another.

In a comparison experiment, PN’s are trained as inhibitory and interneurons as excitatory. In short, this experiment showed selectivity is not a property of excitatory neurons, and also that connectivity of inhibitory neurons remained dense.

In a comparison experiment, PN’s are trained as inhibitory and interneurons as excitatory. In short, this experiment showed selectivity is not a property of excitatory neurons, and also that connectivity of inhibitory neurons remained dense.

III-14 A theory for learning with a constrained weight distribution. Ben Sorscher, Weishun Zhong, Daniel D. Lee, Haim Sompolinsky

Sorscher et al. presented work extending the classic results from Gardner (1988) regarding the capacity of a multi-layer perceptron. Herein the capacity is defined as the fraction of patterns with

with

that are separable by a linear classifier

with margin

. The unconstrained capacity

was given in Gardner (1988) and the authors find that the constrained capacity is given as

where

for some distribution

The authors then asked how the capacity changes when q is constrained to be more biologically plausible -it’s been known for a while that biological neural networks have asymmetric, heavy-tailed distributions e.g. log-normal. Surprisingly the change in information content is proportional to the Wasserstein-2 distance between a Gaussian measure and the target distribution i.e.

The authors then asked how the capacity changes when q is constrained to be more biologically plausible -it’s been known for a while that biological neural networks have asymmetric, heavy-tailed distributions e.g. log-normal. Surprisingly the change in information content is proportional to the Wasserstein-2 distance between a Gaussian measure and the target distribution i.e. , which can be thought of as distance along a statistical manifold parametrizing conditional probability distributions. The authors also experimented with constraining the weight during training, using an alternative updating scheme whereby the performed descent on the weights and then using optimal transport to ensure that their distributional assumptions were satisfied.

III-38 Modeling large-scale brain network dynamics in response to electrical stimulation. Yuxiao Yang, Shaoyu Qiao, Omid Sani, Isaac Sedillo, Breonna Ferrentino, Bijan Pesaran, Maryam Shanechi

Neuromodulation technologies have played a big part in the treatment of various diseases and brain related injuries. However, due to previous technological limitations, models underlying these advancements have their shortcomings. Biophysical models are usually disease-specific, highly nonlinear, and difficult to fit across a group of patients, and data-driven models are usually implemented offline or limited to a small brain region. The authors develop dynamic input-output (IO) models to explain the response of local field potential (LFP) in real time to electrical stimulation simultaneously across many brain regions. They use a linear state-space model (LSSM) as the framework, and develop a multilevel-noise modulated pulse train as a means of stimulation. These were implemented in closed loop on two primate models where the input stimulation and resultant power features of the LFP were used for IO modeling. Furthermore, the functional controllability of the network was tested, by seeing how effective stimulation at one node could drive the others. This was hypothesised and later confirmed to explain variability in their model’s prediction accuracy. What was found was that the dynamic IO models did well in predicting the LFP response under electrical stimulation when compared with other common models. Furthermore, resultant dynamics showed both damping and oscillatory behavior, which could be accurately captured by their model.

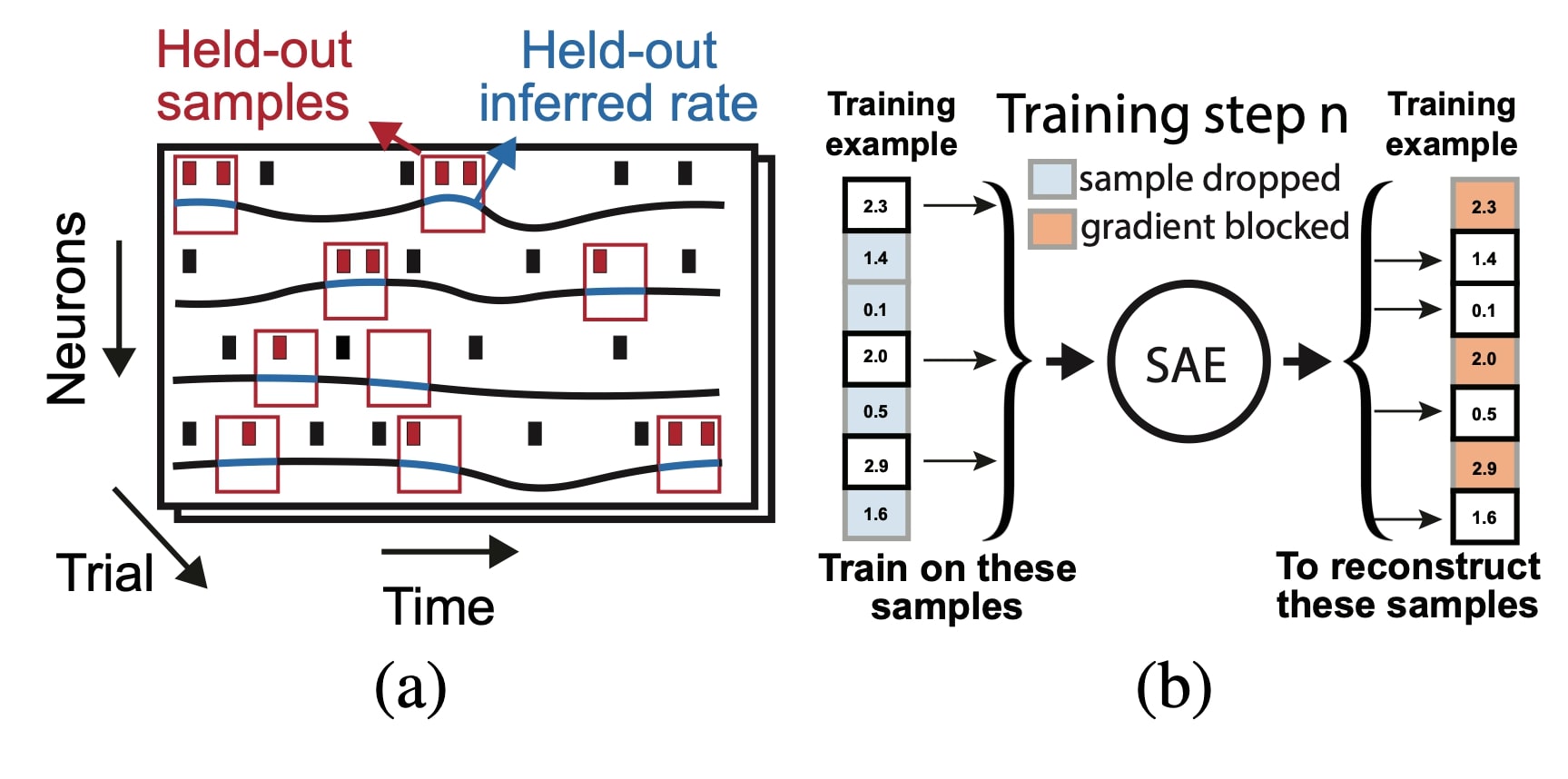

III-117 AutoLFADS: A large-scale neural network training framework for generalized estimation of single-trial population dynamics. Mohammad Reza Keshtkaran, Raghav Tandon, Diya Basrai, Sarah L. Nguyen, Raeed H. Chowdhury, Hansem Sohn, Mehrdad Jazayeri, Lee E. Miller, Chethan Pandarinath

They showcase how to tune LFADS’s hyperparameter efficiently and advertise their online service (a trend in the community?).

Basically they utilize speckled holdout cross-validation (randomly holdout single entries in the neuron by time matrix, How to cross-validate PCA, clustering, and matrix decomposition models · Its Neuronal) and Population Based Training PBT. Briefly, PBT is a method to train many models in parallel, and it uses evolutionary algorithms to select amongst the set of models and optimize HPs.

III-118 Mixture of Poisson Models for Neural Correlations and Coding.Sacha Sokoloski, Amir Aschner, Ruben Coen-Cagli

Correlated fluctuations in response to fixed stimuli are often burdensome when trying to analyze neural data. The author seeks a rate based model of population coding that can maintain the flexibility of those under the maximum entropy framework. Under this line a conditional mixture of poisson (CMP), which is conditionally the maximum entropy distribution is examined. First, it is shown that finite mixture models may be formulated as exponential harmoniums (a product exponential family) under certain conditions relating the mixture parameters and the natural parameters of the product exponential, categorical exponential family.

This allows for the derivation of an expectation-maximization algorithm to fit the proposed model to large-scale data. On synthetic data the derived expectation-maximization algorithm is compared to standard SGD and EM results that do not take advantage of the exponential harmonium property giving the following results. As seen on a model generated from the ground truth (which is also a CMP) the derived approach is able to capture the mixing weights as well as the pairwise correlations of the 20 neurons.

This allows for the derivation of an expectation-maximization algorithm to fit the proposed model to large-scale data. On synthetic data the derived expectation-maximization algorithm is compared to standard SGD and EM results that do not take advantage of the exponential harmonium property giving the following results. As seen on a model generated from the ground truth (which is also a CMP) the derived approach is able to capture the mixing weights as well as the pairwise correlations of the 20 neurons.

In an experiment using real data from the response of macaque V1 neurons to oriented gratings the model is also able to fit the data adequately. In this case the captured correlations are not entirely representative of the ground truth, however a large amount of information about these correlations is still captured by the model.

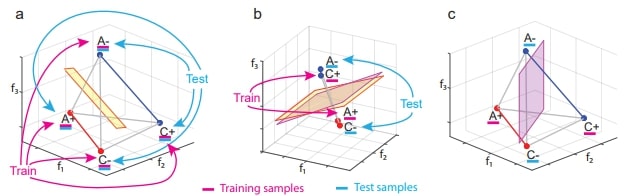

Workshop. Non-canonical neural responses: Where do they come from and what do they do? - Abstract representations: neural responses and their geometry. Stefano Fusi

The authors claim a variable is encoded in abstract format if the a linear decoder trained to report the value of the variable can generalize to new situations (previously unseen combinations of the values of other variables). They call this ability to generalize “cross-condition generalization”. Their task has 3 variables: stimulus, context (hidden) and value (reward). Context determines correct stimulus-response combinations. If each neuron’s activity is random for each stimulus-response combination, a context decoder trained on a subset of trials will be able to decode context from held out trials but this representation is not abstract. To construct an abstract representation, one would need to incorporate information about the shared context of different instances into the geometry of the neural activity (for example clustering together neural responses from the same context). This clustering in space would allow a decoder trained only on trials in which the animal is rewarded to correctly decode context in trials in which the animal is not rewarded (different values of variables). Cross-condition generalization performance (CCGP) measures the performance of a decoder trained and tested on different types of trial conditions. They show recordings from 3 brain regions: hippocampus (HPC), dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex (DLPFC), and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). They see that context and value are encoded in abstract format in the 3 of them while action is not abstractly encoded in HPC.