COSYNE Workshops, Day 1 Part 1

Workshop Speakers:

- Gordon Berman

- Adam Calhoun

- Mark Schnitzer

(Written by David Hocker)

Before the first day of COSYNE workshops we arrived with an ominous “There’s a huge snowstorm coming tomorrow. HUGE!” which didn’t fail to deliver:

The view from our hotel room on the first night

and the aftermath of the storm

So with the prophecy of the storm now validated, and the recent news of my friend ripping his tendons from his kneecap while skiing, I used these as universal signs to stay indoors that day and celebrate warmth. And kneecaps. That means I’ll be giving you a rundown of the talks I checked out during the workshops.

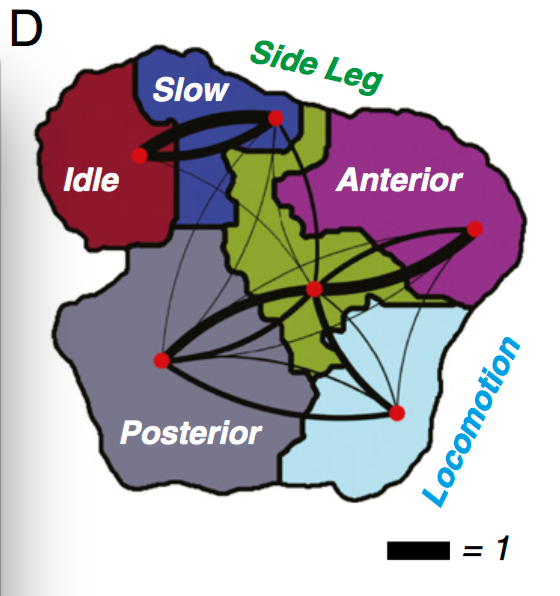

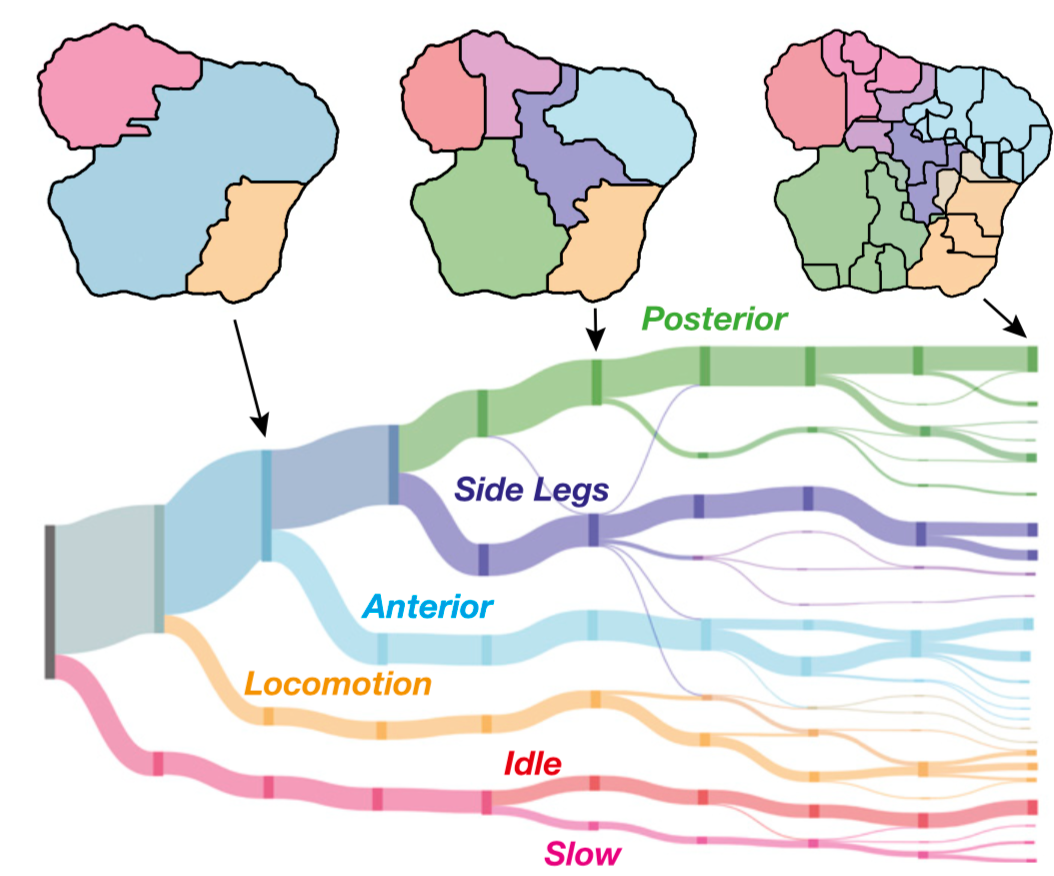

Since this is my first time at COSYNE, I had no idea what to expect in terms of the conference, but the climate here is outstanding. There is so much stimulating work being done, and the workshop component allows you to dive into more of the topics more tailored to your own personal tastes and interests. My problem has been just like a kid in a candy shop, though: I want to see all of it! I decided to focus the morning primarily on the session for automoated tools for high dimensional neuro-behavioral analysis organized by Adam Calhoun, Talmo Pereira, Scott Linderman, John Cunningham, and Liam Paninski. I heard some great talks about automating the analysis of characterizing animal behavior form experiments, beginning with Gordon Berman giving a great talk entitled “Predictability and hierarchy in animal behavior.” Here he followed up on a traditional mode of conceptualizing behaviors from Karl Lashley, such that individual actions can lead to a hierarchy of other behaviors that are more relevant from an evolutionary standpoint. One of the other ways to start getting at this hierarchy of behaviors though is how both Gordon and Adam Calhoun conceptualized their hierarchy, which is terms of timescales of behavior. Basically, short timescale actions like a fly moving in one direction or the other may be part of a longer timescale behavior such as pursuit or investigating a mate. Using that hierarchy idea as a backdrop, Gordon discussed his code to categorize behaviors using a clustering method in a totally automated fashion. Plug for his code: github.com/gordonberman

(A behavioral map of fly movements, taken from Gordon’s PNAS paper).

Once this code had partitioned up streams of behavioral videos into discrete behavioral maps, Gordon started asking some really cool questions about how transitions in this behavioral space occurred over time. In order to get at how the timescale of activity changed the interpretation of behaviors, he demonstrated how longer timestep partitioning of the behavior map shows really intuitive structure, just like the hierarchical organization that Lashley discussed. The last part of the talk investigated the time course of these behaviors as trajectories through the behavioral map.

(Hierarchical structure of fly behavior that arises as more and more clusters are used to explain the observed behaviors, adpated from Gordon’s PNAS paper. The size of the branches denotes the relative amount of time that a fly spent in that cluster)

Take home message: Tools to generate these behavior maps in an automated fashion rock, and you can start finding relationships between behavioral data that you might have missed, and also give you a great new tool to start understanding behavior at different hierarchical levels.

- References: check his PNAS paper.

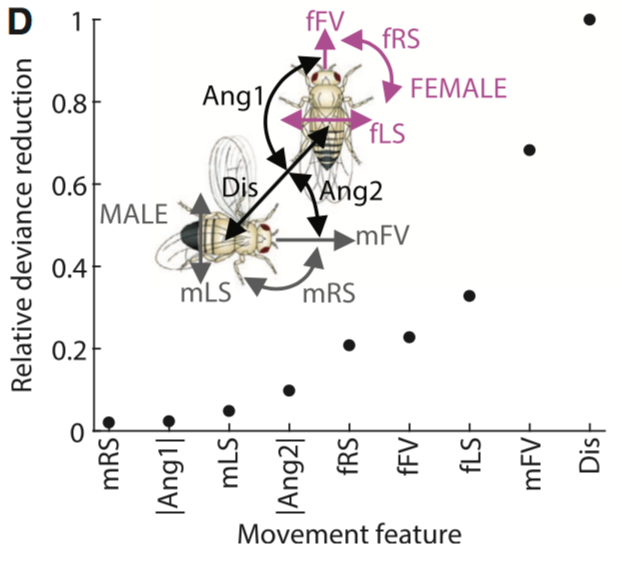

Adam Calhoun also touched up the idea of longer-timescale behavior embedding shorter timescale actions, and his work moved more into effective predictive models for showing how courtship behavior in flies, aka their cute little wing-flappy songs, can be predicted from other behaviors such as how close the flies are, and how they are oriented towards each other. I got a chance to do a rotation in Mala’s lab last summer as part of Princeton’s NAND program, and I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity. So its really neat to see this work grow from where I saw it last year. The Murthy group was hitting this problem of predicting male fly song from behavioral parameters from tons of different angles, and Adam’s newest contribution was to incorporate the idea of a longer timescale “state” of the fly that might influence how those behaviors such as male fly velocity might have different importance. This has been one of the major themes of COSYNE this year (state-dependent computation), and its neat to see it even using purely behavioral information. Adam built a classifier of the song type based on behavioral covariates, but the newest feature was to combine it with a hidden Markov model different states among which the fly can randomly transition. Not only did this dramatically improve the the predictability of a particular fly song time (the louder, more staccato’d pulse song P1), but it also provides a model that can better match with our intuitive idea of hierarchal behaviors. Most of this is unpublished, so I can’t give away the particulars of how those states are interpreted, but keep an eye out for their work.

(Schematic of behavioral parameters used in building the classifier for song type, taken from their Neuron article)

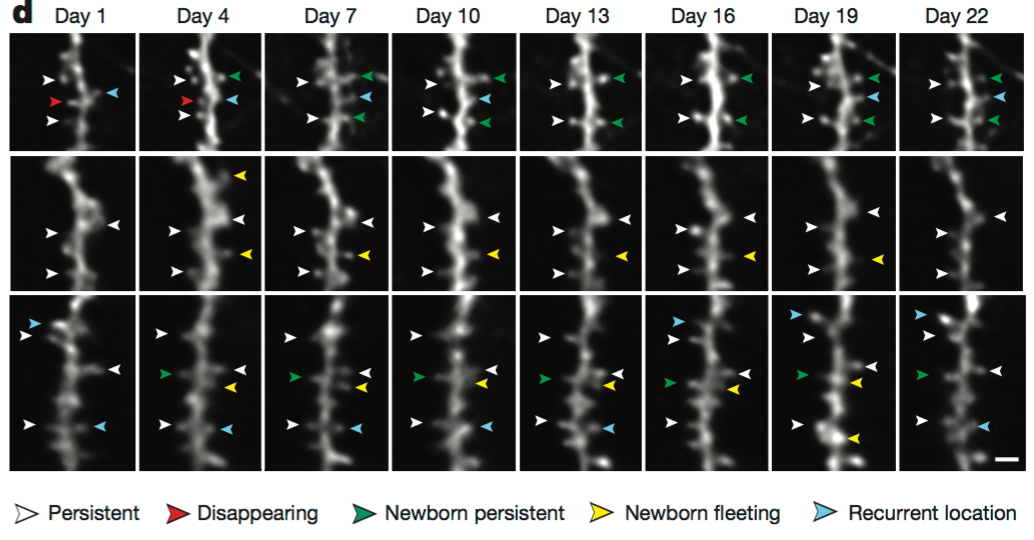

I jumped ship on behavior to check out Mark Schnitzer’s talk during the end of the morning session on “Neural ensemble dynamics underlying associative learning and memory.” I was super excited to see this another main theme of COSYNE, network-level computation, in a context that I haven’t had a ton of exposure to yet, and it didn’t disappoint. The talk was broken into two main experiments. The first was on the remapping of the neural code for place cells in CA1 mouse hippocampus over time. They had previously shown that entire populations of dendritic spines in CA1 cells can grow and decay over the course of a month, so what does that imply for their populaiton coding properties?

(Loss and gain of dendritic spines in CA1 cells of a mouse. Entirely new populations of dendrites can arise over the course of a month. Figure taken from their Nature 2015 paper)

I had been hearing a lot about place cell remapping over the past few weeks, and this was another flavor of that kind of process in CA1. What Mark found is that by taking two-photon calcium imaging data of freely-behavior mice (moving in a 1D track), that place fields that were encoded by neurons on one day actually faded away, and individual neurons developed new place fields. The main observation from Mark’s talk though, was that at the population level there was still a relative amount of preservation of the place field.

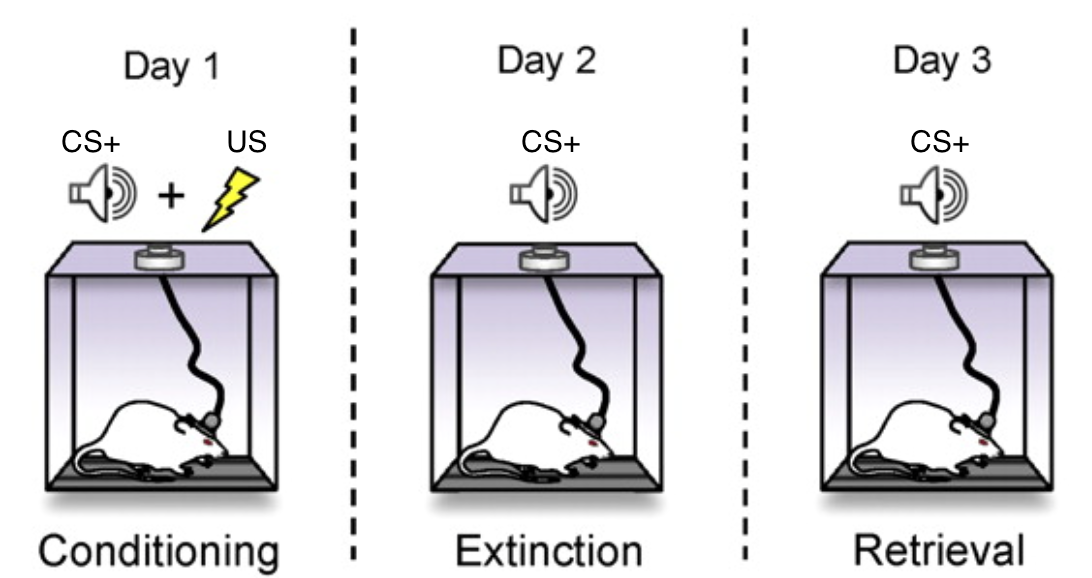

The coolest part of the talk was that he took some conceptually similar recordings in the amygdala during fear conditioning tasks. Again, I saw another COSYNE theme here which was to probe traditional ideas of learning, memory consolidation, and recall. This work was unpublished, so I won’t go into too much detail, but essentially Mark looked at the population-level activity of encoding a conditioned stimulus that led to a shock, and then observed how the basolateral amygdala encoded that same stimulus after extinction training. So for people that aren’t familiar with this type of emotion research paradigm (I certainly am no expert, and have only seen it a few times up until recently), the idea is that a mouse can hear two separate tones, called the conditional stimulus (CS). CS+ is usually the tone that is given right before an unconditioned stimulus (US) is presented, namely a shock. CS- is a different tone that does not lead to the US. There are also neutral stimuli thrown into the mix as well. So, you can first play CS+ without any shocks. just to get the mouse used to hear it. Then you teach the mouse to feat CS+ by presenting it to them a few times (usually only need a few), then they start to associate CS+ with a shock. Then, you teach them to not fear CS+ through extinction training, where you present CS+, but then you don’t shock them. After another day or so, you can test whether or not the animal is still afriad of the stimulus by playing CS+ again, without a shock.

(Schematic of extinction training. Figure adapted from this paper).

Mark’s main result was that how the mouse encoded CS+ after extinction training differently than how it did both after learning to fear it, and differently than before the fear conditioning every occurred. So the amygdala encoded CS+ in a totally new way that was not seemingly related to the older memories of the stimulus. The main conclusion here is that extinction training may actually be a newly learnt memory, not a reversal of the association with fear. There seems to be link to some of the fMRI results that were discussed at the main meeting by Elizabeth Phelps. Check out that work when it comes out. It looks like a really cool data set.

- References: Nature 2015 paper