COSYNE Workshops, Day 1 Part 2

Workshop Speakers:

- Konrad Kording

- Andrew Welchman

- Elizabeth Buffalo

(Written by David Hocker)

I started the afternoon session of Day 1 listening to Konrad Kording’s guiding thoughts on how neuroscience should really be doing a reality check on some of its basic assumptions underlying the ways that we try to understand the brain. It was refreshing to hear the community reflecting on their approach at such a high level (consequently, others were asking the related questions at exactly the same time as COSYNE via The Atlantic). Konrad’s talk focused on the need to understand the brain through the process of reverse engineering it, and how trying to build understanding from ground-up techniques such as tuning curve analysis of a neuron’s response to a stimulus have allowed some pervasive assumptions about their interpretation. He hit on three main assumptions that have some mounting evidence against them:

- The things that neurons respond to are straightforward to guess.

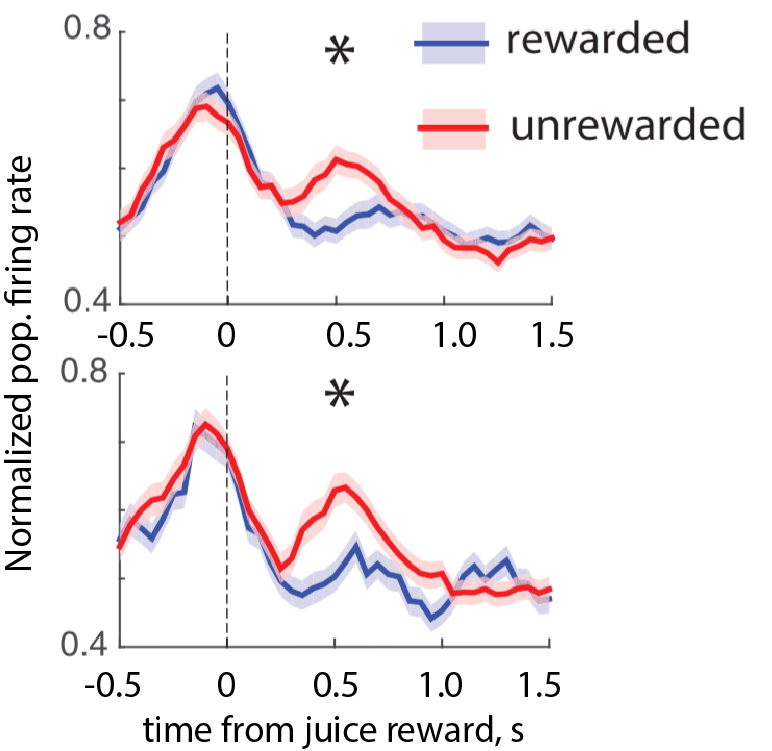

If you believe that regions of the brain are compartmentalized based upon function, then you would live and die by that assumption. But the realization that the brain works in concert with many of its parts simultaneously is nearly pervasive in neuroscience these days. Konrad called out just a few examples that make it hard to interpret tuning curves as being functionally relevant for only one thing. Examples: Motor neurons can actually respond to reward outcomes, and expectation of a later event occurring can be encoded in the visual cortex.

(Example of M1 neurons during two separate recording sessions that encoded reward by having population-wide firing rates that were higher after an unrewarded trial than a reward trial. Figure adapted from here)

-

The response of neurons to stimuli are linear, or a least nearly linear. Most things are just easier to deal with if they have a linear response, so it’s a good regime to work in, analytically speaking. But if the response to behaviors or stimuli are nonlinear, this can absolutely be a dangerous assumption to make. Konrad’s main example here was that V4 neurons that encode color are quite nonlinear with respect to changes in the types of scenes that are shown. Maybe that’s buried in Pavan Ramkumar’s cosyne poster?

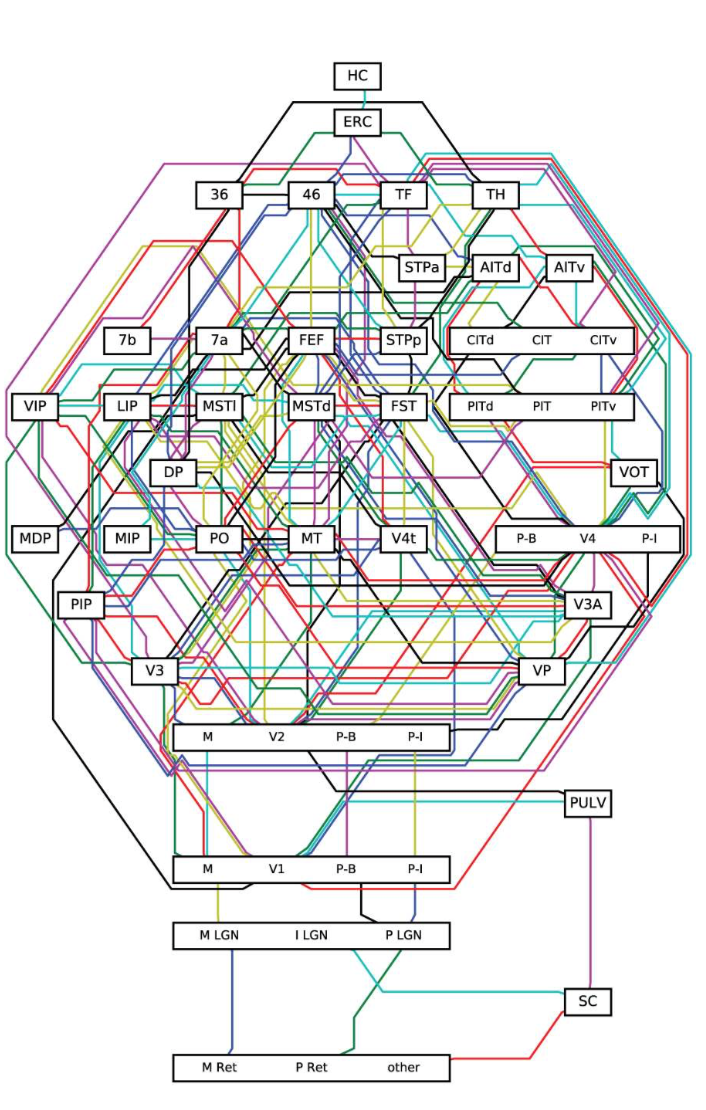

- The brain processes and hands off information to different functional regions in a step-by-step process. I didn’t catch a ton on this topic, but he did pull up a schematic from Van Essen’s paper for functional connections in the brain from his and Eric Jonas’ recent article:

(Functional areas of the brain, and their connections as we currently know them. Used in the PLOS Comp. Bio. paper and taken from Van Essen’s paper)

These are all fair points to consider challenging in neuroscience, and there are active attempts in the field to address all of them that are not necessarily reverse engineering related (i.e, you don’t need deep learning to start chipping away at these traditions in the field). Plenty of people are using generalized linear models to incorporate nonlinear responses of spiking neurons to regressors, and some of these models do take a more agnostic approach to the important behavioral and task covariates by including nearly everything about the task at hand to adequately capture the statistical structure of the data, for example Memming Park’s 2014 Nature Neuroscience paper (shameless plug for my PI here). And there are more experimental studies that are trying to understand the coupling of different brain regions during cognitive tasks. For example, Carmen Varela gave a really captivating talk at the main workshop on the joint activity in premotor cortex, thalamus, and hippocampus during sleep; as well as Karel Svoboda’s work on cortical activity flow during decision making. These are precisely the kinds of data that can be used to probe Konrad’s critique of these step-by-step information processing models.

From there I switched things up and went to visual processing talk by Andrew Welchman titled “On sensing what’s not there.” This was a super fun and accessible talk that hit upon one of the less-considered insights from Wheatstone’s 1838 discussion of binocular vision, that binocular vision renders certain pieces of an image visible to only one eye due to ocular occlusion. Basically, only one of your eyes will be responsible for the input of some part of the overall image being processed by your brain. Andrew discussed how this privileged information in only one of your eyes can help discount possible false interpretations of the image being shown, which he termed the disparity energy model. Keep a lookout for that work.

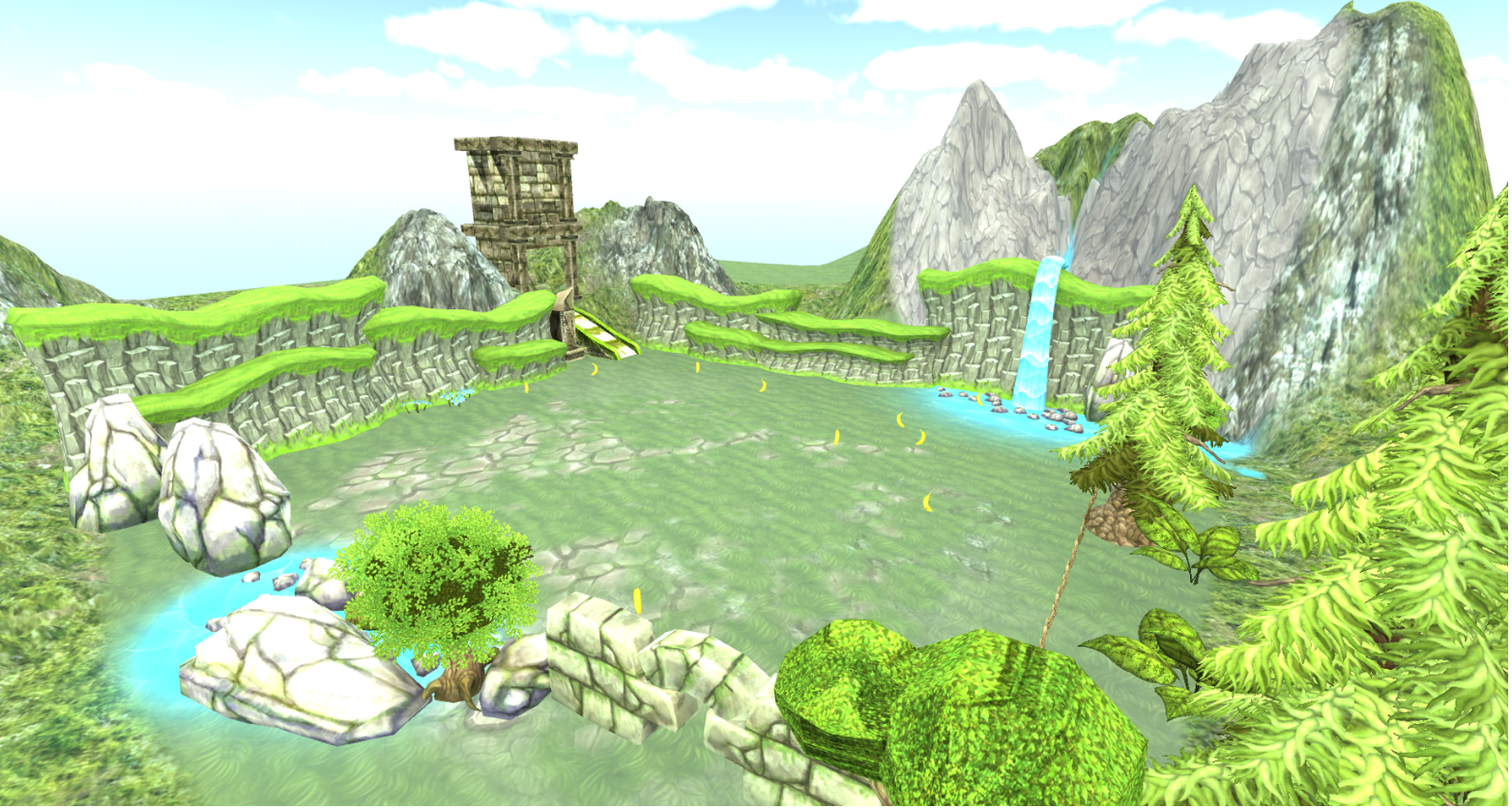

Next I headed off to see some of the coolest experiments discussed at all of COSYNE. Monkeys in virtual reality eating pretend bananas. Elizabeth Buffalo from U. Washington used multi-electrode recordings and eye-tracking software to identify the spatial navigation cells often explored in rodent navigation experiments (grid cells, border cells, and place cells), but instead used them while a monkey was learning to navigate a VR environment using a joystick, given the tounge-in-cheek goal of capturing oversized bananas that earned them real-life snacks. What was cool about this experiment (apart from the training complexity of getting a monkey to operate a joystick and learn the game in the first place!) was the difference in when a grid cell or place cell fired for monkey compared to a rodent. Rats and mice explore their environment locally, so place or grid field was active when the animal was in that particular location in space. Monkeys explore a new environment more like us though, and heavily use vision to navigate. Consequently, Elizabeth found “visual” grid and place cells in entorhinal cortex and hippocampus that fired when a monkey looked at a particular point in space. The road to finally locating these place cells was not easy though, and forced the group to implement some novel electrodes and to really refine their VR environment. It turns out that monkeys need a reasonably complex environment to make individual places within it memorable, so they decked out their second-generation game for the monkeys with a lot more foliage and other natural features.

(The original VR environment for the monkeys. Pretty bare with only a few landmarks. Elizabeth said that even her research team had a difficult time mapping out the environment, themselves.)

(The enriched VR environment with more features. This was the style of game that activated place cell selectivity in the monkeys.)

The place field cells work is quite new, but you can read about their related work on grid cells and eye-tracking software in their Nature paper and their PNAS paper.